Research and Fieldwork

In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan, the strongest storm ever recorded, destroyed most of Tacloban City. The coastal community of Anibong, which is made up of mainly slum swellers, was significantly affected. Thirteen tanker ships washed up along the shore, and one of them killed family members of a household I got to become friends with during my PhD. After Haiyan a 40 meter no build zone was put in place and households were evicted.

When I visited from 2015-2017, relocation and demolition had not taken place so to me, the disappearance of a community was still theoretical to me. To me, eviction and demolition were politically caused and largely political ideas so when I visited Anibong in 2024 and saw a community I had visited frequently completely gone, it was emotional.

However, the feeling of loss that I experienced that day is only a tiny fraction of the displacement physically, emotionally, culturally, economically, socially and politically that Haiyan survivors experienced. These losses are rarely captured in research but they should be because they can contribute to empirically supported policies and improve future relocation programs.

In 2022, our team (Tyler Valiquette, Dr. Gerson Scheidweiler & I) went to Pacaraima, Brazil’s border city with Venezuela to do participant observations in Brazil’s many humanitarian shelters. What we saw at the official border crossing was actually a lot of unofficial ones - trochas - informal paths that migrants take that are often dangerous and ruled by paramilitary and gangs. In this video, I am showing my students not just the trochas but also how porous or fuzzy borders are. A border is not always a big fence or a wall. Instead, here it is represented only by tiny white posts.

We also use trochas and the border as a lens to examine frontiers as places almost outside of the law where violence is permissible. In that zone, there remains a contest over the monopoly of violence. The stories of violence, robbery and sexual violence that Venezuelan asylum seekers shared with us were horrific. This horror was only matched by some of the stories that LGBTQ+ refugees shared about discrimination by police officers who didn’t help them when they were being beaten up because they were Venezuelan or trans Venezuelan asylum seeker sex workers who shared that they were kidnapped and trafficked.

Fieldwork in the ASEAN Region and Latin America

Climate Change Displacement Dialogue Speaker Series 2024-2025.

Research Expertise & Case Studies

Ethical Strategies for Adaptation & Relocation

-

The Sea to coastal communities is not just a physical geographic element of nature, it is their livelihood, their culture, their history and their home. My research found that resettlement projects often move coastal communities away from the sea to cheap rural lots of land. while economically feasible for humanitarian and government organizations it causes significant damage to the communities, including generational trauma. Community members tell me they worry their children will lose their connection to the sea and therefore the identity of their people.

In this light, we understand that the process of relocation needs to be ethical, community-informed and deliberate. Yet, that is not what we see on the ground, specifically when adaptation and relocation projects are being blended and often on purpose.

The relocation of communities after a disaster is a humanitarian concern, the long-term relocation of a community to adapt to the challenges of climate change is a development project. For either to be successful, extensive community consultations are required, but too often, disaster capitalism incentivizes governments to relocate coastal slum communities so that hotels can be built along the coast, and all of it is done under the banner of climate adaptation. -

Su, Y. (2025, August 22). Why Climate Visa Lottery Schemes Are Not the Answer. Foreign Policy.

Bruni, V. & Su, Y. (2025). Imagining alternative migration futures for the Pacific Island States. Forced Migration Review. 76.Su, Y. (2024). The Australia-Tuvalu deal shows why we need a global framework for climate relocations. The Conversation.

Critical Analysis of the “Build Back Better” Approach

-

During my PhD research, I frequently visited people’s rebuilt homes after Typhoon Haiyan, and I often found that people aspired to build their homes back “better” after the disaster. After all, the slogan of disaster risk reduction over the last decade has been “build back better,” but is the slogan universally good? Can bad come from building back better? On the face of it, no, but upon deeper inspection, yes, building back better can result in building back worse if the proper materials and knowledge are not there.

Specifically, I found that poor households inspired to build 2nd floors because it was “better” did so with scrap metal, tarps and rotting wood - the same materials that will fly off roofs in the new storm and kill people. So I ask - build back better for who? By who? With what? -

Su, Y., & Le De, L. (2020). Whose views matter in post-disaster recovery? A case study of “build back better” in Tacloban City after Typhoon Haiyan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51.

Curato, N., & Su, Y. (2018). “Bitter back bitter? Five lessons five years after Typhoon Haiyan”. New Mandala.

Su, Y., Mangada, L., & Turalba, J. (2018). “Happy-washing: how a “happiness campaign” hurt survivors”. New Mandala.

Extreme Climate Change Adaptation

-

Through my fieldwork, I discovered the phenomenon of climate change adaptation-induced displacement, specifically when it comes to infrastructural adaptation projects such as sea walls. As global efforts to adapt to climate change intensify, the negative consequences of these adaptations are becoming increasingly apparent. This research synthesizes existing literature to explore how adaptation measures, particularly large-scale infrastructural projects, can displace vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing inequalities and creating new challenges for affected communities. Working with my colleagues, we introduce the concept of climate change adaptation-induced displacement, or adaptation-induced displacement, to capture how adaptation projects can intentionally and unintentionally displace and relocate vulnerable populations in the name of adaptation.

-

Su, Y. (In Prep). Displaced by Adaptation: Climate Change Adaptation-Induced Displacement Due to Infrastructural Projects. Global Environmental Change.

South-South Queer Forced Migration

-

Since 2019, Tyler Valiquette (UCL) and I have undertaken high-risk research into the homophobia, xenophobia, transphobia, and gender-based violence experienced by Venezuelan LGBTQI+ asylum seekers in the border cities of Pacaraima, Boa Vista, and Manaus in Brazil and Cúcuta in Colombia. Conducting extensive fieldwork in refugee camps, LGBT refugee centres as well as encampments in Brazil and Colombia, our research is focused on identifying the protection gaps that LGBTQ+ asylum seekers face, especially high-risk groups such as trans Venezuelan asylum seeker sex workers and queer indigenous displaced peoples from Venezuela. These groups are at much higher risk of extreme violence, exploitation and human trafficking and are often overlooked in humanitarian and government responses.

Our research aims to challenge and expand the traditional scope of queer migration studies by exploring the dynamics of south-to-south migration among LGBTQ+ Venezuelans in Colombia and Brazil. Unlike the conventional narrative that portrays migration primarily from oppressive states in the Global South to more welcoming societies in the Global North, this work delves into the complexities faced by LGBTQ+ migrants within the Global South itself.

Current literature on LGBTQ+ migration often overlooks the south-to-south migration paths, assuming that these migrants will find solace in LGBTQ+-friendly communities. Our research seeks to fill this gap by presenting empirical research that illustrates the contrary—showing that LGBTQ+ migrants often face significant challenges, not only from the broader societal structures of their host countries but, crucially, from their own ethno-national diaspora. -

Su, Y., Valiquette, T. & De Oliveira Cunha, C. (2025). Networks of South-South Queer Forced Displacement: A Case Study of the Social Capital of LGBTQ+ Venezuelan Asylum Seekers in Northern Brazil. Global Networks.

Su, Y., (2023) No One Wants to Hire Us: The Intersectional Precarity Experienced by Venezuelan LGBTQ+ Asylum Seekers in Brazil during COVID-19. Anti-Trafficking Review. (Open Access)Su, Y., & Valiquette, T. (2022). ‘They kill us Transwomen’: Migration, Informal Labour and Sex Work among Trans Venezuelan asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Brazil during COVID-19. Anti-Trafficking Review. (Open Access)

Cowper-Smith, Y., Su, Y., & Valiquette, T. (2021). “Masks are for sissies: the story of LGBTQI+ asylum seekers in Brazil during COVID-19”. Journal of Gender Studies, 31(6): 755-769.

Valiquette, T., Cowper-Smith, Y., & Su, Y. (2021). Casa Miga: A case of LGBT-led, transnational activism in Latin America. In Zhou, R. Y., Goellnicht, D., & Sinding, C. (Eds.), Sexualities, Transnationalism, and Globalization: New Perspectives. Routledge.

Su, Y.,Valiquette, T., & Cowper-Smith, Y. (2021). Surviving Overlapping Precarity in a “Gigantic Hellhole”: A Case Study of Venezuelan LGBTQI+ Asylum Seekers and Undocumented Migrants in Brazil amid COVID-19. Statelessness and Citizenship Review, 31(1), 155-162. (Open Access)

Valiquette, T., Su, Y., and Scheidweiler, G. (2021). Unwelcomed: Examining Brazil’s Broken Promise to Venezuelan refugees amid COVID-19. Humanitarian Alternatives. (Open Access)

Remittances, Social Capital & Post-Disaster Recovery

-

Based on decades of research in the Philippines, “The Myth of Remittances,” my book project challenges the prevailing narrative that remittances—funds sent by migrants to their families back home—are a reliable tool for crisis recovery and poverty alleviation. As the humanitarian landscape grows more volatile and aid agencies collapse, remittances remain the last reliable lifeline – now further strained by Trump’s USAID shutdown, forcing migrants to carry the burden of international development. But remittances are not foreign aid. They are personal money transfers meant to support families, not replace internationally funded initiatives that address poverty, disaster response, and infrastructure at the regional or national level.

“The Myth of Remittances” takes a unique focus on the human and household-level experiences of remittances during crisis recovery, offering a critical counter-narrative to the global optimism surrounding remittances. Based on extensive fieldwork, over 1000 household surveys from 2017 to 2023 and a decade of research, the book provides empirical data that challenges the assumption that remittances are a reliable safety net for all and a reasonable substitute for foreign aid.

-

Su, Y. (2022). Networks of Recovery: Remittances, Social Capital and Post-Disaster Recovery in Tacloban City, Philippines.International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 67. (Open Access)

Su, Y., & Le De, L. (2021). Uneven Recovery: A Case Study of Factors Affecting Remittance-Receiving in Tacloban, Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan. Migration and Development.

Su, Y., & Tanyag, M. (2019). Globalising Myths of Survival: Post-disaster Households after Typhoon Haiyan.Gender, Place & Culture, 26(3).

Eadie, P., & Su, Y. (2018). Post-Disaster Social Capital: Trust, Equity, Bayanihan and Typhoon Yolanda. Disaster Prevention and Management, 27(3), 334-345.

Su, Y., & Mangada, L. (2017). A Tide that Does Not Lift All Boats: The Surge of Remittances in Post-Disaster Recovery in Tacloban City, Philippines. Critical Asian Studies, 50(1), 1-19.

Preibisch, K., Dodd, W., & Su, Y. (2016). Pursuing the Capabilities Approach within the Global Governance of Migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(13), 2111-2127.

Local-Indigenous Knowledge, DDR & Adaptation

-

There’s a growing recognition by scholars that local-indigenous knowledge can make important contributions to both disaster risk reduction and managing environmental change. Dr. Ginbert Cuaton and I research the local-indigenous knowledge and practices of the Mamanwa indigenous peoples in Basey, Samar, after Typhoon Haiyan struck the Philippines in November 2013.

We argue for the meaningful participation of local communities including Indigenous Peoples should be the focus of local DRR actors. -

Cuaton, G., &Su, Y.(2023).Promises and pitfalls of social capital to climate change adaptation of an Indigenous Cultural Community in the Philippines.Third World Quarterly.

Cuaton, G., &Su, Y. (2020). Indigenous Peoples and the COVID-19 Social Amelioration Program in Eastern Visayas, Philippines: Perspectives from Social Workers. Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 9(3), 43-52. (Open Access)

Cuaton, G., &Su, Y. (2020). Local-indigenous Knowledge and Practices on Disaster Risk Reduction: Insights from Post-Haiyan Philippines. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 48.

The Political Ecology of Critical Mineral Mining in Southeast Asia & Latin America

-

In the communities that I work with in Central and Southern Philippines, critical mineral mining kept emerging as a pressing issue over the last three years. While I initially noted their concerns and re-centred my work on climate change migration and adaptation, the local protests and impacts on indigenous communities grew too loud to ignore. And when I turned my attention to the topic, it was clear why their concerns were so significant. This stat really stuck out to me: 69% of global mining projects are located on, or near, Indigenous lands and 40% in conflict settings.

This reality was not in any of the electric vehicle ads or any campaigns in the Global North for the need to transition to low-carbon economy. Instead, electric vehicles, even if they were giant CyberTrucks, were marketed as good and sustainable. Yet, these electric vehicles require six times the amount of minerals compared to traditional vehicles. This has ignited a global rush to mine these finite energy transition minerals and metals (ETMs) like nickel and copper.

Global demand for nickel is projected to increase by 60-70% by 2040, and copper demand is expected to be 200-350% higher by 2050 than in 2010. China propels much of this ETMs demand, now nations are expediting mining to combat its dominance and prosper from this resource boom. However, the fast-tracked extraction and production of ETMs poses significant risk to terrestrial and ocean ecosystems, human health, and peace and human mobility. Weak governance, unequal costs, a colonial history of extraction, and environmental harm in ETMs-rich developing countries, sustain the current inequities, violence, and imbalanced resource geographies caused by mining. Hence, ETMs extraction reflects ‘carbon colonialism’, where resources are taken and profited from by external actors, but the source bears the hidden costs38. Indeed, the urgent need for ETMs has not allowed for sufficient recognition of the impact extraction will have on local lives, such as Indigenous Peoples (IPs), who face high displacement risk.

With a transdisciplinary team of scholars from Harvard, Stanford, and Berkeley, we have been working on a very easy to make colorimeter that can detect toxins in soil and water samples so that indigenous communities can understand how mineral extraction is polluting their water and soil and the health implications of that. This project is novel because it recognizes IPs' dual exposure to mining and climate change, which protects their resilience and prevents further vulnerabilities, maladaptation, and loss and damage. Our project aims to compare mining sites in the Philippines, Indonesia, Peru, and Ecuador, which are all ETM-intensive countries with high populations of IPs.

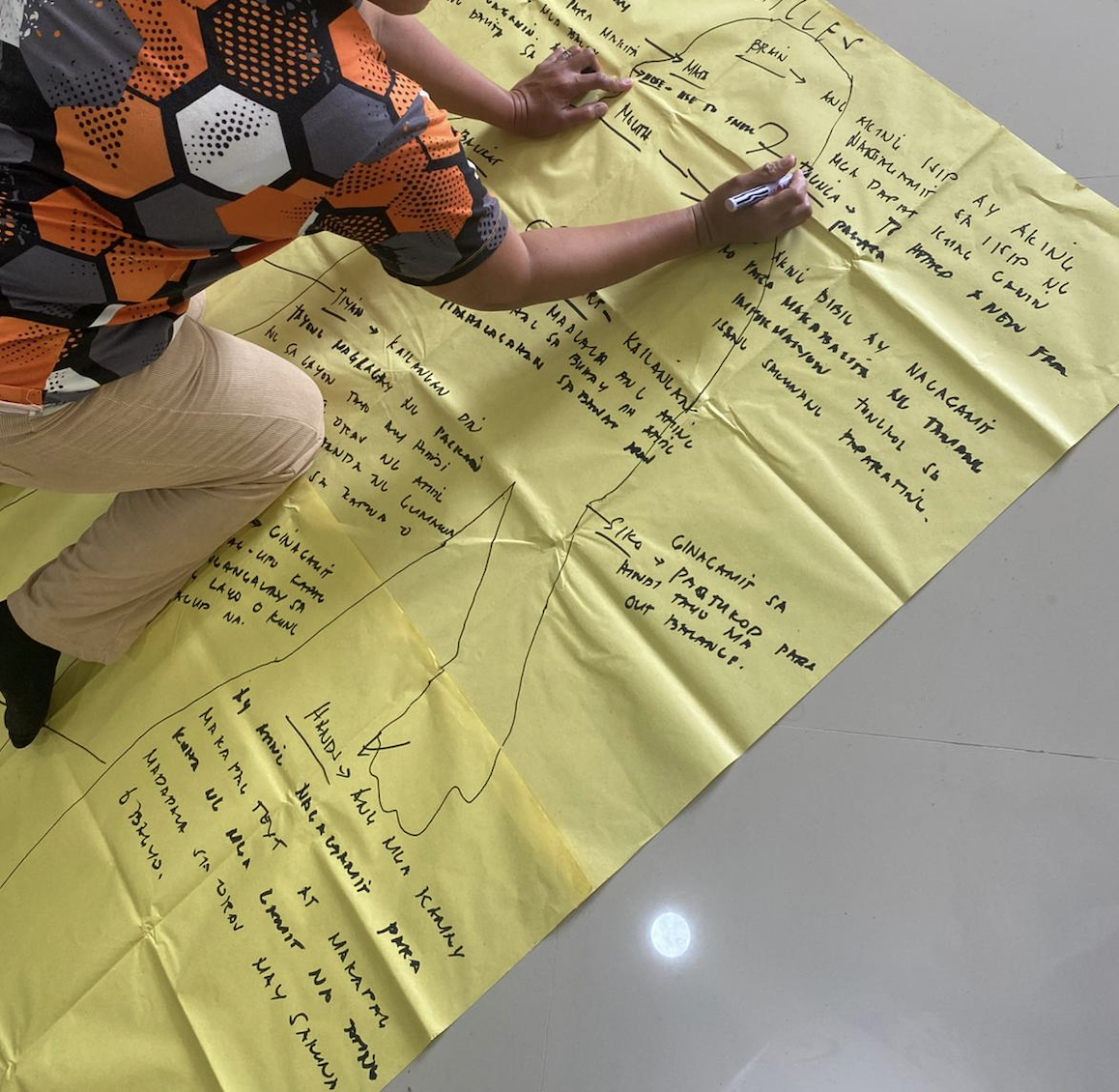

Arts-based, Visual & Participatory Methods

-

During my PhD, I discovered the power of participatory methods to allow people to open up their world to you and tell their own stories. While my PhD committee suggested traditional methods o surveys and interviews, these methods alone often fail to capture the full complexity of peoples' lived experiences, which are often emotional, sensory, and nuanced. Art-based methods offer innovative ways to explore these dimensions by using arts such as visual arts, performance, storytelling, and music as tools for data collection, representation, and analysis. My experience with arts-based methods have shown me how these methods can provide new insights into people's personal and collective impacts, amplify their voices, and contribute to social justice by challenging dominant narratives.

Over the last decade, I have not just been using participatory methods like photovoice, videovoice, participant-aided sociograms and bodymapping in my fieldwork, I have also been promoting it to others as a more holistic, empathetic, and transformative approach to studying migration, one that values the subjective experiences and identities of migrants in ways that traditional methods may not.

The aim is to expose more people, particularly students and early career scholars, to a range of creative and innovative research approaches, demonstrating how these methods can enrich international development and migration studies by capturing the emotional, sensory, and personal dimensions of migrants' experiences.

-

Valiquette, T., & Su, Y. (2024). Combining Photovoice and Videovoice for Participatory Research: Visual Storytelling with LGBTQ+ Refugees and Migrants.The Journal of Participatory Methods.

Su, Y. (2022). Networks of Recovery: Remittances, Social Capital and Post-Disaster Recovery in Tacloban City, Philippines.International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 67. (Open Access)

Migrant TikTok: The Struggle for Digital Power

-

I never imagined I would be researching TikTok, let alone writing a book about it. Still, once I saw how drastically different migrants were representing themselves on TikTok than on other platforms and how strongly the media and states were weaponizing their videos, I couldn’t look away.

Working together with the talented Tegan Hadisi (MPhil student at Oxford & my former student at York), we examined the content of 100 Migrant TikTok content creators. This was a different type of fieldwork that required a completely new set of skills, but the experience was stimulating and world-altering. I cannot wait to share our book with you so your worldview can be changed forever, too.

-

Our book “Migrant TikTok: The Struggle for Digital Power” (co-authored with Tegan Hadisi) is under contract with Fernwood Publishing for publication in 2026.